CV

Kazuho Ohya

Kazuho Ohya

Ohya was born in Aichi Prefecture in 1997, where she is currently based. After graduating from the Art Department of Aichi Prefectural Asahigaoka High School in 2016, she went on to earn her degree in Oil Painting from Kanazawa College of Art in 2021.

The artist creates narrative works with a focus on oil painting and bodily expression. Active since 2019, Ohya primarily uses oils to depict ‘human stories’, incorporating elements from early modern Western painting to contemporary Japanese animation. In recent years, their practice has especially centred on the representation of the female body and its narratives, with subjects spanning from biblical texts to the artist’s own lived experiences.

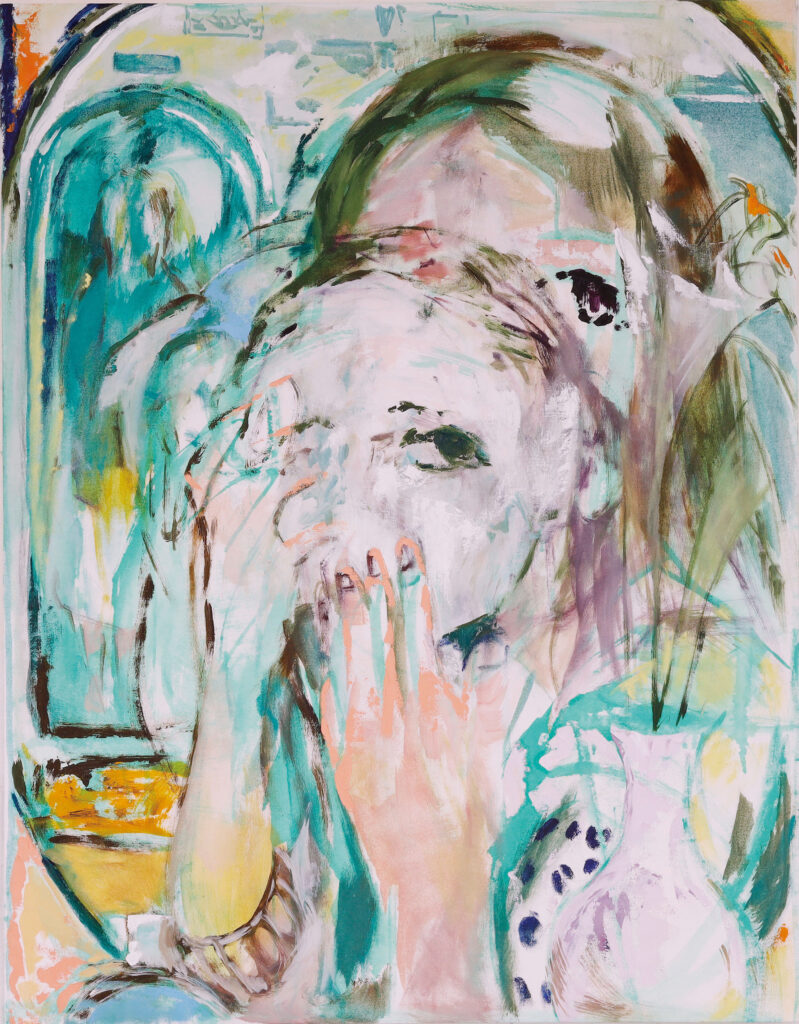

Mirror

2021 – Turner Award (Grand Prize, 2020)

Oil and poster colour on F50 canvas

The painting depicts a woman, wearing a mask and standing before a mirror. With its wavering lines akin to drawing and the fact that masks had become part of everyday life at the time, the work was recognized as a ‘contemporary piece that evoked the sudden changes of daily life’, leading it to receive the Grand Prize.

Although I had been studying painting in a specialized way since junior high school, I continually struggled with the divide between academic works and anime/manga works. Mirror was created as a first step in breaking away from that divide.

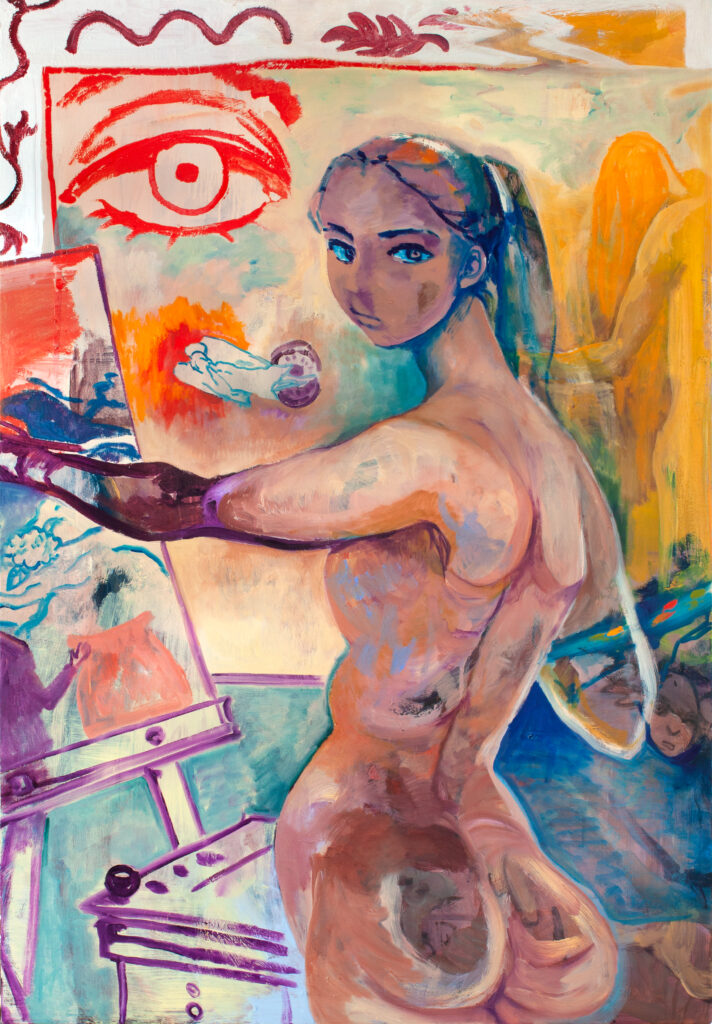

Only God Knows

2023 – Idemitsu Art Award (Selected Work)

Oil on F100 canvas

This artwork depicts a nude woman at work painting, her gaze cast directly toward us as viewers. Within the work, a large watchful eye can be seen, as well as an angel overseeing her. The woman herself is depicted as extending beyond the frame of the painting to create the artwork. This interplay of the positions between the viewer and viewed forms a nested structure. The thematic depth and the strong visual impact of the work were highly regarded, and earned the work its recognition.

The basis of this work lies in my own experience as a nude model, as well as my experience in drawing from them. Standing at the lectern as a teacher and living as a member of society have led me to reflect anew on the weight of those experiences and on how they are viewed by society. This work was created with those reflections in mind — questioning the strangeness of the female position, both as ‘the one who looks’ and ‘the one who is looked at’, and the issues that arise from it.

作家活動

Though I’m Based in Aichi, I mainly exhibit in Tokyo. I have also shown work in Taiwan and Hokkaido, among other places in Japan and abroad. My work aims to create narrative paintings that focus on oil painting and bodily expression.

Since childhood I have always loved stories. At first, I wanted to become an illustrator and draw illustrations for light-novels, which led me to study art. But once I entered academic art education, I began to feel a certain doubt. Perhaps you also hesitated in junior high or high school art classes to draw something ‘manga-like’. I grew frustrated with the fact that although I started studying art in order to improve at manga-style drawing, I could not actually practice it in class.

At the same time however, it was the 2010s, when works like Takashi Murakami’s ‘Superflat’ paintings and Akira Yamaguchi’s illustration-inflected paintings were emerging. As a high-school student I admired them and was encouraged by their example. Like them, I tried in my own way to sneak manga-esque imagery into school and art-school assignments, attempting to bring it into the realm of ‘academic’ painting.

The situation didn’t change much at university either. But as my perspective broadened and I came to know more art students of my own generation, I realized that bringing manga-like images into painting was not necessarily bad. In fact, many others were doing the same, making their own academically grounded manga-style paintings. This raised a new question for me: if this were the case, then why is manga expression still consistently shunned in academic contexts? Searching for the reason behind this avoidance has become a fundamental driving force in my work.

So, what is ‘manga-like’ expression? One could name many traits: highly deformed faces and bodies, flowers in the background to symbolize emotions, and so on. But I believe that at its root lie narrativity and the expression of time. Stylized renderings of faces and emotions make a story’s characters easier to grasp visually, while speed lines or the panel frame itself can directly express the passage of time. These core elements of manga expression can also be found in oil painting. Willem de Kooning’s fierce brushstrokes evoke emotion and temporal flow. Jenny Saville’s paintings, where moving bodies are held on the canvas in lines reminiscent of drawing with multiple hands depicted, are not so different from the way manga shows movement — are they?

I make narrative paintings with this way of thinking in mind, and the stories I am currently telling are women’s stories — including my own. Limiting myself to gender may feel narrow today, but I still feel that telling women’s histories from a woman’s perspective remains lacking in society.

One representative work, Only God Knows, came out of my experiences both as a nude model myself and as an artist drawing from them. Women have long been cast in the role of ‘being looked at’, yet they are no different from men — of course, they are also the ones who look. I trust I am not alone in feeling discomfort at this social convention. Compared to men, there are very few examples of women expressing themselves as the ones who look. That is why I want to encapsulate the world as I see and feel it within the frame of the oil-painted canvas and send it out into the world.

Another essential element of my practice is the method itself: painting in oil on a flat surface. Oil paint can sometimes feel inconvenient because of how slow it is to dry, but it’s precisely this property, as well as its colour and plasticity that suit my way of working — moving back and forth among many different images within a single painting.

ステートメント

印象派やデ・クーニングから連なる筆致の身体性と、私の日常の観察、そしてフェミニズムの視点を重ねることで、現在の社会にある、見る/見られるといった構造そのものや、人と人のあいだに生まれる様々な距離と、距離や言葉が身体に刻む痕を表現する。社会のスケールで起きることは個人の身体に沈殿する。私は狭い生活圏で拾った出来事を、油彩という器に注ぎ直し、言葉になる直前の感情として共有したい。

幼少期から私の日常には秘密があり、知るには早すぎた「身体の現実」を抱え、育った。以来、私の身体は他人の視線、沈黙と喧騒のあいだで居場所を探しつづけ、安心と不安、親密さと拒絶を日常として生きてきた。

こうした過去を語ったとき、ある男性は私を「開かれた城」と喩えた。その喩えを聞いた瞬間、怒りと悔しさがこみ上げたと同時に、離れたいけれど近づき中身を知りたいという矛盾や、殴りたい衝動と諦めに近い静けさが一度に押し寄せた。私はその瞬間の速度と重さを絵画に翻訳し、彼にそう言わせたあらゆる社会通念と制度を作品の衝撃で抉り出したい。

このように、私が画面に留めたいのは、壮大な事件ではなく、一言で体温が変わるような出来事の連続そのものである。絵画は精神と身体の両方に触れる実践の場であり、「精神」と「肉体」が同時に目に見えるように立ち上がる場所だ。そこで私は、奪われた私本来の体験を見える形で取り戻していく。

油彩の厚みや乾く速度から生まれる色や絵肌は、存在の物質的な実感や曖昧な距離を形とし留める。アニメ・漫画に由来するコマ割りのような線や構図は呼吸が絶たれる緊張感を生み出す。そして胸・腰・手などの具象的表現は身体を標本のように固定し、対して線や色で表現される抽象的表現は、視線や気配といった流動するものとして存在する。このように現代日本の表象であるアニメ・漫画表現、静止と流動の間に、作られた痕と、その痕を作ったものに触れ返す意思を画面に定着させていく。

私は、自分の中にある矛盾、社会への怒りや、人間同士の愛情を信じる気持ち、そうしたものすべてを等身大で提示したい。鑑賞者がそれを見て、自分の傷や喜びと重ね合わせ、少しでも息がしやすくなるのなら、これほど嬉しいことはない。

The process of my latest work, genesis3

Rough sketches

The female body is drawn on a large scale, keeping softness in mind. I produced more than five sketches and often choose the one with the most ambiguity of expression. At this stage, no particular reference materials were used.

From rough sketch to underdrawing

The ground is prepared with a cream-coloured Cansol undercoat. Because it is an oil-based ground, it produces strength and lustre. The cream colour is also complementary to blue, which gives depth to blue tones. Using the rough sketch as a base, the drawing is carried out freely.

Developing the painting

With a flat brush wider than 20 cm, the female body is expressed on a large scale. Due to its large size, paint is applied in many different ways to build up texture — for example, throwing loosened paint onto the surface — in order to maximize the variety of textures.

Adding key elements

As an element of the painting, it was judged that a single female figure could not sustain the scale of a size-200 canvas, so an eye was added. Also, relying on imagination alone made the body feel weak in expression, so from this stage, a mirror was used to depict it more realistically.

Strengthening the body

In addition to using my own body, I also referred to previous sketches and photographs to express a figure that matched the soft image I was aiming for this time. By adding the eye, the narrative element of the work also became more concrete, and the brush began to move more smoothly.

Defining the theme

By painting a woman on the right-hand side, the theme and direction of the work further solidified. From there, while following the theme, the necessary imagery and colours were arranged to balance the composition and move toward completion.

Finished work

In the completed painting, the woman on the left becomes God (Yahweh) from Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. At the lower right, Adam’s finger receiving the breath of life was also painted. The whole piece was carefully finished using glazing techniques and masking tape.

It was only at stage ⑥ that the decision was made to make this a work about the creativity of women in giving birth and nurturing. In my practice, the themes and motifs within a painting often shift back and forth. This is not so much a sign of lack of planning as it is what makes the work interesting. For me, a painting is both a tool for organizing my thoughts and a kind of milestone for my ideas. When organizing thoughts, I often consider something different first, and then use it as a stepping stone to create something new. The plasticity of oil paint corresponds to the plasticity of my own thinking.

Contact Us

作品等に関するお問い合わせはこちらから。

For inquiries about the artwork, please contact us here.